0406 - Jay Valentine

Jay Valentine patrolled center field in 1977 and 1978 for the Indianapolis Clowns, the last of the Negro League baseball teams. During our conversation, he referenced a handful of things and people upon which you may want to do more research. Consider this page to be your “liner notes” for the episode so you can follow along.

Me and Jay Valentine after recording our interview at his home in Ohio

Miami Giants

Though the Miami Giants’ history is shadowy at best, several accounts credit Johnny Pierce, a numbers runner and bootlegger, and Hunter Campbell with the team’s founding.

Pierce’s and Campbell’s choice of “Giants” as team moniker is not surprising; black teams frequently adopted “Giants,” so if fans saw “Giants” on an announcement or advertisement, they could assume it was a black team.

Ethiopian Clowns

By 1941, the team was calling themselves the Miami Ethiopian Clowns, but when they became an independent barnstorming club, they shortened that to just the Ethiopian Clowns.

The team’s Ethiopia reference was seen by some as exploitation of black sympathy, which encouraged Negro league owners to oppose adding the Clowns to their ranks.

Syd Pollock

Syd Pollock was instrumental in promoting and popularizing the Clowns and developed them into a nationally-known combination of show business and baseball.

Pollock worked as a booking agent for several clubs starting in the late 1910s before becoming an executive with the Havana Red Sox / Cuban House of David / Pollock's Cuban Stars from 1927 to 1933.

Pollock served as the booker, general manager and eventual primary owner of the Ethiopian/Indianapolis Clowns from 1936 to 1965.

“Prince Joe” Henry

While still fielding a legitimate team, the Clowns also toured with several members known for comic acts — sort of a baseball version of the Harlem Globetrotters, including Joe "Prince" Henry.

Injuries put an end to a two-plus-season stint holding down second base for the Memphis Red Sox in the early 1950’s, but Henry resurfaced in 1955 with the Clowns.

Henry's showmanship at third base during two seasons in Indianapolis earned him the nickname "Prince Joe."

In 1943, the team relocated to Cincinnati, where they became the Cincinnati Clowns.

Move To Buffalo

The 'Buffalo Clowns' were a very successful team, as they were already the Negro League Champions upon arriving in Buffalo in 1951, and went on to win 2 more championships in 1952 and 1955.

During their 5 year span in Buffalo, the Clowns played all of their games at home at Offermann Stadium on Michigan and East Ferry.

1950 Clowns

The Clowns rejoined the Independent League and won their first league championship in 1950.

Here, King Tut (left) boxes with Spec Bebop during a Clowns game on August 1, 1950.

(Photo By Dean Conger/The Denver Post)

Champions

The Indianapolis Clowns won the Negro American League championship in 1951, 1952, and 1954.

1977 - The Clowns’ 48th Season

Jay Valentine joined the team in 1977, playing Center Field and participating in the show that season and the following year, in 1978.

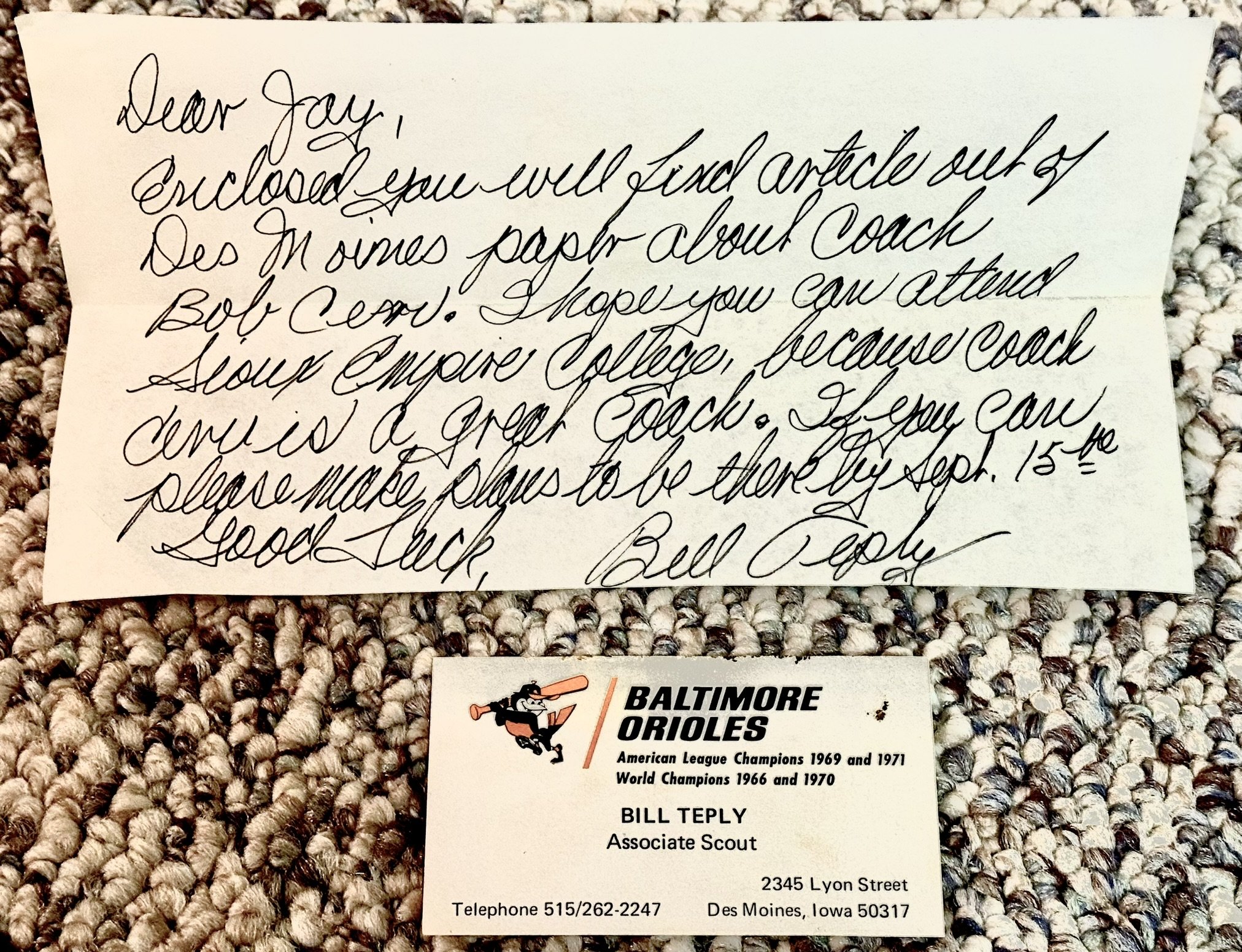

After playing with the Clowns, Jay attended Sioux Empire College for two years where he played for former New York Yankee and World Series champion Bob Cerv.

Traveling Circus

The Clowns played in every state in the US, as well as Canada, Mexico, Cuba, and Puerto Rico.

The largest crowd the team ever played in front of was 41,127 fans in Detroit.

The smallest crowd was only 35 fans in Lubbock, Texas, but there was an active tornado happening during the game.

The Clowns once played in a town with a population of just 476 people, yet managed to bring out 1,372 fans to the game.

The Clowns continued to play exhibition games as a barnstorming team until they finally disbanded in 1989, but not before they made history and broke barriers for more than half a century.

Jay Valentine

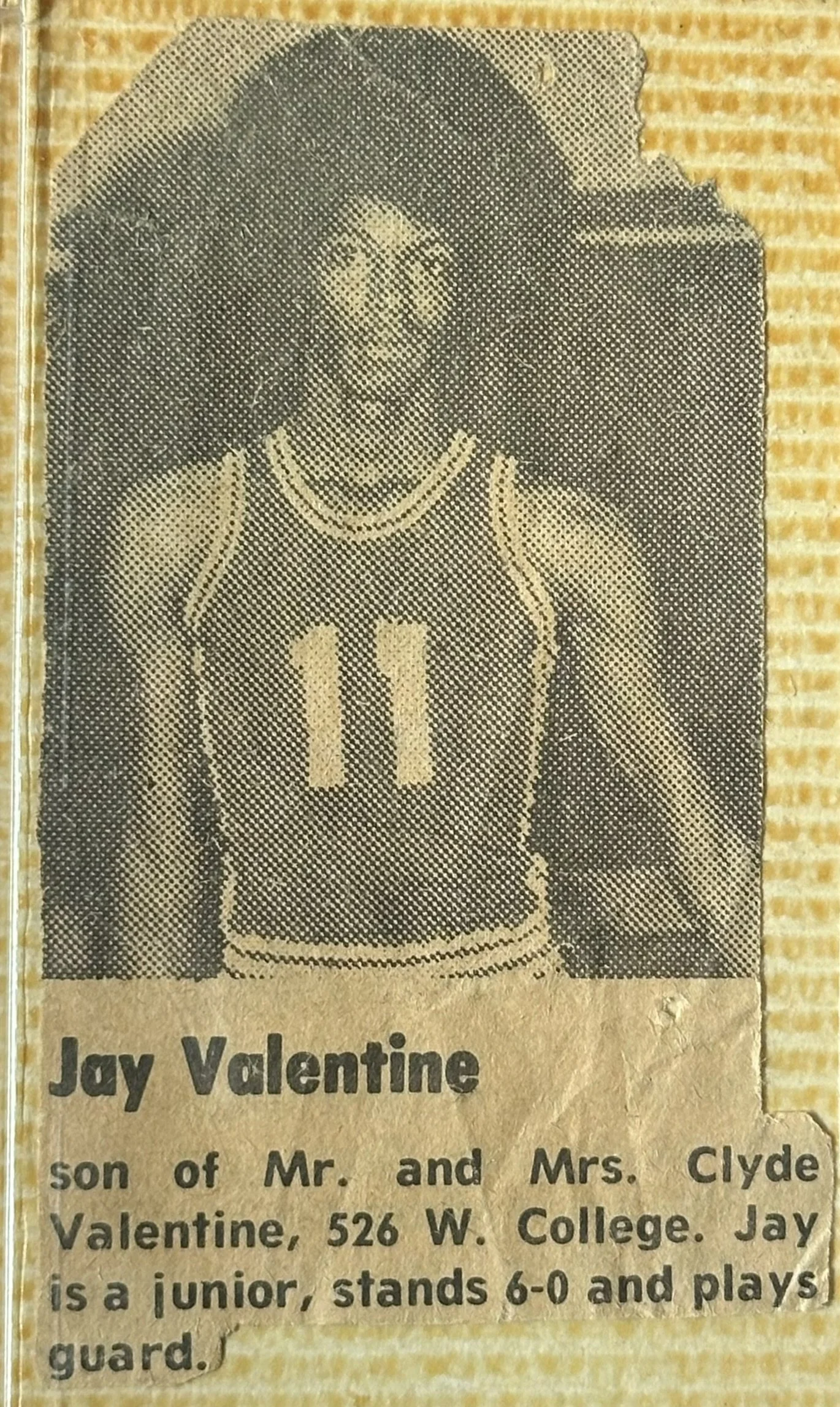

Jay was born in Chillicothe, Ohio in 1957, but his dad took a job in Oberlin so the family moved there in 1966.

Jay’s dad was one of ten children, and Jay was one of five.

Jay’s parents are pictured here with Jay’s nephew.

Young Jay

Since there were so many men in the family, there were always gloves laying around the house. Jay grew up learning to love watching and playing baseball as a Cleveland Indians fan.

Vada Pinson

Vada Pinson played as a center fielder for 18 years (1958–1975). The best years of his career came with the Cincinnati Reds, for whom he played from 1958 to 1968 as a four-time National League All-Star.

Pinson was 5’ 11” and 170 pounds, and batted and threw left-handed. He combined power, speed, and strong defensive ability, and was Jay’s favorite player growing up.

Radio executive Clifford Evans conducted audio interviews of baseball players during spring training in the early 1960s. You can listen to the interview he conducted with Vada Pinson on February 26, 1962 HERE.

Vic Davalillo

Vic Davalillo played as an outfielder for the Cleveland Indians (1963–68), California Angels (1968–69), St. Louis Cardinals (1969–70), Pittsburgh Pirates (1971–73), Oakland Athletics (1973–74), and Los Angeles Dodgers (1977–80).

Davalillo, who batted and threw left-handed, was a leadoff hitter known for his speedy baserunning and capable defense, all qualities which made Jay adore him.

Davalillo also had an exceptional career in the Venezuelan Winter League, where he is the all-time leader in total base hits and career batting average.

All told, Davalillo played for 30 years in the U.S., Mexico, and his homeland of Venezuela, compiling more than 4,100 base hits during his career.

Mickey Rivers

Mickey Rivers played from 1970 to 1984 for the California Angels, New York Yankees and Texas Rangers.

As a Yankee, he was part of two World Series championship teams, both defeating the Los Angeles Dodgers, in 1977 and 1978.

"Mick The Quick" was generally known as a speedy leadoff hitter who made contact and was an excellent center fielder, so it’s no wonder Jay liked him.

César Cedeño

César Cedeño was a center fielder from 1970 to 1986, winning five consecutive Gold Glove Awards between 1972 and 1976. As a member of the Astros, he helped the franchise win its first-ever NL Western Division title and postseason berth in 1980.

Cedeño became only the second player in MLB history to hit 20 home runs and steal 50 bases in one season (1972), and the only major leaguer to do so in three consecutive seasons (1972-74).

Vada’s Shoes

One of the things that always stood out to Jay about Vada Pinson was his shoes. It wasn’t just Jay who noticed, though. Teammates also praised the way Pinson took pride in his appearance, shining his shoes to a high gloss.

Former Reds second baseman Tommy Helms: “His game and practice shoes were shined brighter than my dress shoes.”

Former Reds manager Sparky Anderson: “He would spit shine those shoes of his every day.”

Curt Flood, who was a year ahead of Pinson at McClymonds High School in West Oakland: “Vada was neat as a pin. He shined his shoes between innings, almost.”

Jay’s Shoes

Did you really think I was going to bring this up in the interview, make you read all of those quotes about teammates commenting on Vada Pinson’s shiny shoes, and then not show you a picture of Jay as a little kid with his shoes all shined? I thought you knew me better than that by now.

Little League

Little League Baseball prohibited racial discrimination when it was founded in 1939, but In 1955, Little League’s rule directly conflicted with Southern laws that prohibited integration. That year, white Little League teams in South Carolina, Florida, and Texas refused to take the field against Black teams as part of a massive resistance to the Brown decision.

Pictured here are Jaycees catcher Richard Morris Jr., Kiwanis pitcher Johnny Lane, Jaycees pitcher Robert East, Kiwanis catcher Gary Fleming, Little Leaguers from Orlando who made history in 1955.

Luis Tiant

Another of Jay’s favorite players growing up was Luis Clemente Tiant Vega, a Cuban pitcher who played primarily for the Cleveland Indians and Boston Red Sox.

"El Tiante" compiled a 229–172 record with 2,416 strikeouts, a 3.30 ERA, 187 complete games, and 49 shutouts in 19 seasons. He was an All-Star three times and a four-time 20-game winner.

Tiant was the AL ERA leader in 1968 and 1972 and the AL leader in shutouts in 1966, 1968, and 1974.

Tiant was the only child of Luis Tiant Sr. and Isabel Vega. From 1926 through 1948, the senior Tiant was a great left-handed pitcher for the Negro league's New York Cubans during the summer, and the Cuban professional league's Cienfuegos in the winter.

Hot Stove League

Jay lived in Oberlin, which is in Lorain County in Ohio. While playing travel ball in the Hot Stove League growing up, his teams would travel to the surrounding counties in Ohio to play games, usually between 30 and 40 each summer.

#28

Vada Pinson (and César Cedeño, actually) wore the number 28 during his playing career, so that’s the number Jay chose to wear when he played ball in high school.

Oberlin High School

Jay went to Oberlin High School and played center field for the Indians in his one season playing high school ball. In the last game of his sophomore year, he hit an inside the park home run against Vermillion.

Unfortunately, before the game, the upperclassmen on the team had purchased beer to drink on the team bus after to celebrate. When the boys cracked them open, the smell of the beer made its way to the front of the bus, where the coaches were.

Every player on the team was suspended, and after the story made its way to the newspapers, the entire team was kicked out of the conference.

American Legion Baseball

American Legion Baseball enjoys a reputation as one of the most successful and tradition-rich amateur athletic leagues. Today, the program registers teams in all 50 states plus Canada. Each year young people, ages 13 to 19, participate.

Since its inception in 1925, the league has had millions of players, including countless who have gone on to play in college and professional baseball, with 82 inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

The program is also a promoter of equality, making teammates out of young athletes regardless of their income levels or social standings.

Scott Fletcher

Sometimes scouts would come to American Legion games in search of talent.

Scott Fletcher was discovered by a scout playing American Legion ball in Wadsworth, Ohio. Eventually, he played 15 years in Major League Baseball, including with the Texas Rangers and two stints with the Chicago White Sox.

George W. Bush named his dog Spot Fetcher after Fletcher while Bush was the owner of the Texas Rangers.

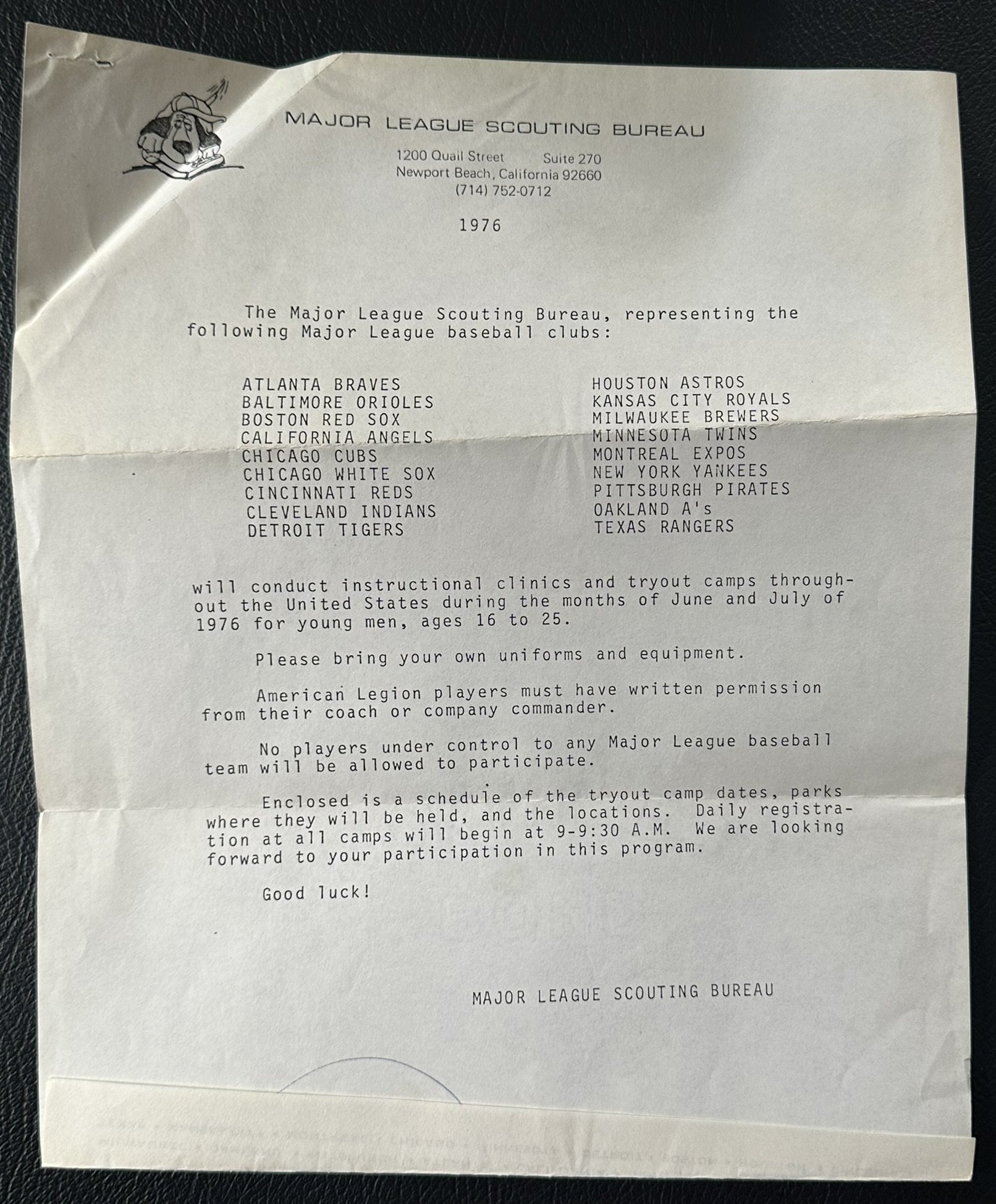

Jay received letters from the Major League Scouting Bureau informing him that there were tryouts all over the country.

Major League Scouting Bureau

These letters served as an open invitation to the recipient to attend any tryout on the enclosed list.

It was up to the player to pay his way to the tryout, and to show up with any equipment and uniforms he may need, but once your name was in the system, you were able to try out on any of the dates and at any of the locations listed.

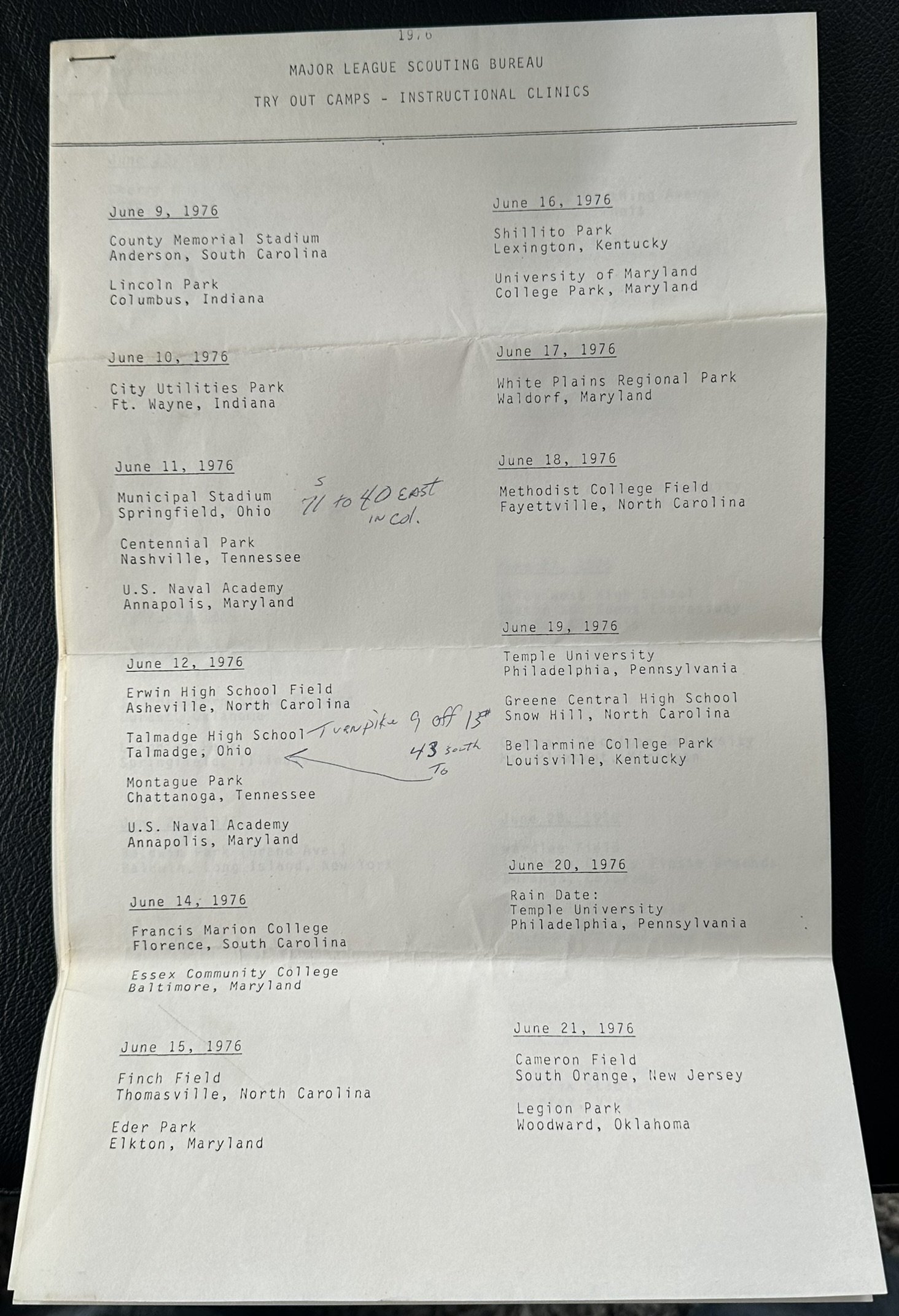

Jay’s Tryout

Though he theoretically could have gone to any of the tryouts on this list (which was multiple pages long), Jay chose to only go to the tryout held on June 12, 1976 at Tallmadge High School in Tallmadge, Ohio.

The name of the school and town is mistakenly spelled “Talmadge” on the sheet. Maybe that was the first test for a player trying out there…

Jay’s handwriting on the page show some basic directions of how he was going to get there.

Just A Kid

In 1976, Jay earned an invitation to the Florida Instructional League in Fort Lauderdale with the New York Yankees.

He got on a plane on January 23, 1976, after finishing his high school credits that December, a semester early.

Steve Hughes

Steve Hughes’ career began with the Pittsburgh Pirates straight out of high school, where he spent nine years splitting time between the Pirates and Reds in the minor leagues. Steve also had the honor of playing for the original Nashville Sounds team.

Since Steve had already been signed by a team, he bought a conversion van and had a little bit of money - at least compared to the other players sharing the house at the Florida Instructional League with Jay.

Steve was a polished infielder, playing primarily shortstop, but he compiled a career batting average of only .218 with 1 home run and 157 RBI in his 655-game career. He had been sent to the FIL to work on his hitting.

A Grueling Schedule

The players of the Florida Instructional League were expected to be at the field and ready to play every morning by 8:00 am. They lived 3-4 miles from the ballpark, and were not supplied with transportation to get to and from home, so it was on them to walk, run, or hitchhike to the park.

The players would taking batting and fielding practice until the actual Major League ballplayers showed up for their training. At that point, the Instructional League players would shag balls for the Major Leaguers.

Around noon, the first round of the day’s practice would end and the players would have a break until about 6:00 pm when they would have to be back at the ballpark for an evening game.

McDonald’s

The players weren’t being paid, so it was on them to either have enough money sent from home, or to get part-time jobs in Florida so they could stay financially solvent for the 8 weeks they were at Spring Training.

While some players stole cars to make ends meet, others got jobs at the local McDonald’s, which was the largest in the world at the time.

Jay worked late nights at the 24-hour restaurant for three days before deciding it wasn’t for him.

Check out this McDonald’s ad from 1976.

Reggie Jackson

Jay shared the field with Reggie Jackson at Orioles Spring Training in 1976.

Jackson retired after the 1987 season with 563 career home runs, the sixth-highest total in MLB history at the time.

Graig Nettles

Jay shared the field with Graig Nettles at Yankees Spring Training in 1976.

Nettles is regarded as one of the best defensive third basemen of all time, winning Gold Glove Awards in 1977 and 1978.

Getting Instruction

The whole point of the Florida Instructional League is for young players to receive instruction on how to become better. After the Major League players would get done practicing for the day, the Instructional League players would continue to work, and that’s when the coaches would tell them what they needed to focus on to get better.

They told Jay, “You’ve got good skills, you’ve got good speed, but your arm could be better. And don’t pull your head off on the ball when you’re at the plate.”

Kenny Lofton

Jay has been described as “Kenny Lofton before Kenny Lofton” because he was a fast center fielder who batted and threw left-handed, batted leadoff, was a great bunter, and stole a lot of bases because he was so fast. I’d say that’s a pretty fair comparison.

Dr. Deuce

Jay wore the #2 on many of his uniforms over the years. He also got on base and he stole bases, earning him the nickname Dr. Deuce.

If you were going to walk him, you were often times walking a double, since Jay was going to immediately steal second in addition to receiving the free pass to first.

At first, his friends were calling him “Dr. Jay” but Jay knew the only “Dr. J” played in Philadelphia. So he became “Dr. Deuce” shortly thereafter.

He has even created his own Dr. Deuce logo, and has custom hats he wears (and sells, if you want to buy one) with the logo on it.

Jay’s Stats

Jay was a great bunter, which was one of the things that helped him have a high batting average. In a July, 1978 issue of the Elyria Chronicle Telegram, it was reported that Jay was batting over .400 after 21 games of the season.

While his career statistics aren’t documented anywhere, and can’t be found online, during his career, Jay would keep his daily stats in a calendar so he could keep track of his progress.

A Great Base Stealer

The most bases Jay ever stole in one game was SIX!!!

But he wasn’t just a volume stealer; Jay was efficient. In four years of college ball, Jay was only thrown out three times trying to steal.

No wonder he had so much swag.

What To Watch For

When Jay was on first base, he would focus on the pitcher’s foot touching the rubber. If that came off the ground, he knew to get back because there was going to be a pickoff attempt. If the pitcher’s front foot lifted off the ground instead, it was off to the races.

But Jay wasn’t only stealing on pitchers. He would pay attention to the catchers, as well. If a catcher was lazy throwing the ball back to the pitcher from his knees, Jay had no problem taking an extra base on a delayed steal.

Jay’s Afro

Here is Jay in 1976 after he came home from Spring Training. Jay said that at its peak, his afro put Oscar Gamble’s to shame.

“It exceeded all proportion,

It could not be contained,

It bloomed round like a dark sunrise,

It glistened in the rain.

The little boys with crew cuts

Or blond locks oh so fair

Would look and cheer with wonder

At Oscar Gamble’s hair.”

—Roy Peter Clark

Gamble was not allowed to keep his afro when he was traded to the Yankees because of their strict appearance policy. At the time, Gamble had a commercial deal with Afro Sheen, but they cancelled the deal when he cut his afro to comply with team policy. Oscar was reimbursed by Yankees owner George Steinbrenner for the $5,000 he lost in the deal.

Eddie Murray

Jay shared the field with Eddie Murray at Orioles Spring Training in 1976.

While Murray would go on to a Hall of Fame career, becoming one of only seven players in MLB history with both 500+ career home runs and 3,000+ career hits, Jay said he didn’t feel intimidated by Murray, or any other player on the field. Jay felt his skills were good enough to compete with any of them.

Paul Blair

Jay shared the field with Paul Blair at Orioles Spring Training in 1976.

Jay said Paul played the shallowest center field of anyone he had ever seen, because Blair knew he could still get back to any ball hit over his head. Apparently, he knew what he was talking about, as his 8 career Gold Glove Awards can attest.

Blair won his first in 1967. After missing out in 1968, he won the award seven consecutive years from 1969 to 1975.

Jay preferred to play deep and come in on balls, so it was amazing for him to watch Blair play.

Curtis Wallace

Curtis Wallace was a 5’ 11” and 183 pound stocky infielder trying to make the Single A team. He told Jay about the Indianapolis Clowns when the two were down in Florida for the Instructional League. That was the first time Jay learned about the Clowns, and that Henry Aaron and Satchel Paige had played for them.

College Ball

Even though the Yankees invited Jay down to Florida to participate in the Instructional League, Jay credits the Baltimore Orioles for his opportunity to play college ball.

George Long

For 25 years, George Long was the booking agent for the Indianapolis Clowns.

Long would operate the Clowns from 1972 to 1983, so he was the team owner at the time when Jay was invited to try out to make the team in 1977.

Since George lived in Muscatine, Iowa, that’s where tryouts were held.

Ed Hamman & Syd Pollock

George Long bought the team in 1972 from Ed Hamman, who had actually been a player on the Clowns until he bought the team from Syd Pollock.

Here, Hamman (left) and Pollock are photographed together at a baseball meeting in St. Petersburg, Florida in 1959.

Ed Hamman

Hamman was known in his playing days for being able to pitch the ball from behind his back or between his legs. He conceived the idea for the oversized glove and bat which remained staples of the Clowns’ show for years.

Here, Hamman (right) is pictured with Richard Elmer "King Tut" King (left) and Ralph Bell, aka “Spec Bebop” (center).

Some Are Called Clowns

When Curtis Wallace arrived with the Clowns after he was called to come play for the team, he was surprised by what he saw.

An excerpt from Bill Heward’s great book, Some Are Called Clowns:

“I figured I'd walk into a hotel and there'd be a bunch of guys in the lobby bobbing their heads and sticking their tongues out with their eyes rolling in big circles. People walking on their hands, juggling balls and bouncing them off their heads…

“You know, Indianapolis Clowns. And I was kind of scared 'cause I figured somebody was going to ask me about my number, if I kicked balls off my feet, did cartwheels, or what, and all I could do was play baseball.”

Birmingham Sam

Birmingham Sam was the Clown Prince of the team when Jay was with the Clowns.

Nate “Bobo” Smalls

Nate “Bobo” Smalls was also a major part of the show, sharing time with Birmingham Sam as the main attractions.

“If He Did It, I Could, Too”

When Jay learned that Henry Aaron got his start in professional baseball by playing with the Clowns, he thought to himself “if he did it, I could, too.”

Roster Sizes

Roster sizes for Negro League teams were usually only about 15-16 players per team. Pictured here is the 1944 Clowns team, featuring rookie Armando Vázquez.

Vázquez followed in the footsteps of his childhood hero, Martin Dihigo, and came to the U.S. to become a Negro Leagues baseball player in 1944.

Checker Aerobus

When Jay was with the Clowns, however, they kept a roster of just 12 players! Why only 12? Because that’s how many could fit in their vehicle: the Checker Aerobus.

George Long

While George Long managed the team in a sense, he wasn’t really the team’s Manager, on the baseball field. That was really left up to the players, themselves, since George really only traveled with the team for a couple weeks out of the year.

Injuries

Jay broke his wrist two times within six weeks one season. He was able to tough it out and stay with the team, performing in the announcer’s booth for part of the time.

But if an injury was really severe, like a broken arm or broken leg or something, usually the player would just be sent home because George Long couldn’t afford to keep a player on the road who wasn’t contributing to the team.

Very Few Off Days

The Clowns would play between 60-70 games in about 3 months time during the summers, sometimes playing 2-3 games in a single day.

Occasionally, the team would play an early game in one town, drive up to 200 miles to the next town immediately after the first game ended, and play a second game that night in the new town.

Marty Kobernus

There were really only three guys on the Clowns who pitched regularly. However, anyone on the team who could throw strikes was allowed to pitch to save those guys' arms since the team played so many games.

The team would just talk amongst themselves to decide whose arms was good to go on any given day, and whoever needed to step up and eat some innings would do so.

Pictured here is one of the Clowns’ regular pitchers, Marty Kobernus.

Traveling

The Clowns traveled to 28 different states in three months while Jay was with the team one year. George Long scheduled all of the games and coordinated everything from back home in Muscatine, Iowa.

Pictured here is Marty Kobernus in the Rocky Mountains.

Negro League players performing “Shadow Ball”

Birmingham Sam

Jay was roommates with the team’s Clown Prince, Birmingham Sam, when they were lucky enough to get either a hotel or a motel on the road.

Juggling

Jay could juggle, which came in handy during the team’s shows. The Clowns had juggling as part of their shows dating back decades.

Here, “Juggling Joe” Taylor shows off his skills. Taylor was an exceptionally good juggler, but his talent didn’t relate to baseball.

Lots Of Time In The Car

Jay played in North Carolina, South Carolina, Alabama, Kentucky, Illinois, Indiana, Wisconsin, Iowa, Missouri, Nebraska, Kansas, Utah, Idaho, Montana, New Mexico, Colorado… 28 states in three months one season.

Pass The Time

“We drank some beers, smoked some cigarettes, and drank some beers” to pass the time in the car on those long drives.

Mike Coco

When your personal car has personalized plates with your name on them, you know you love to drive. Second baseman Mike Coco rarely gave up the wheel when traveling with the Clowns.

Road Trip Gags

There wasn’t really room to play cards or do anything other than drink, sleep, or bust each other’s balls in the car. The hours and hours the teammates spent joking with each other made them a really tight-knit group. Here, Coco and Marty show just how close teammates can be.

Traveling In The Checker Aero

The members of the team got pretty good at reading maps over the course of their time playing with the Clowns. If there were ever any issues, they could always call George Long in Muscatine, Iowa, who would help them out.

Staying In Touch

When the team was on the road, the players would have friends and family (and girls) send mail to this address in Muscatine. Then, George would send that mail to the team’s next stop on the road, since he knew their schedule, and the players could stay in touch with everyone that way.

Girls

If players met girls on the road, they might follow the team for a couple games. But if they wanted to stay in touch after that, they would have to send mail to their favorite player through George Long in Muscatine.

George Long

George Long spent 67 years as the organizer and coach of the semipro team in Muscatine, Iowa. He managed Babe Ruth and Henry Aaron, and managed against Satchel Paige and Dizzy Dean.

In an interview with the New York Daily News when he was 89-years-old, when asked how long he would manage, he said “I’m going to give it up when I get old.”

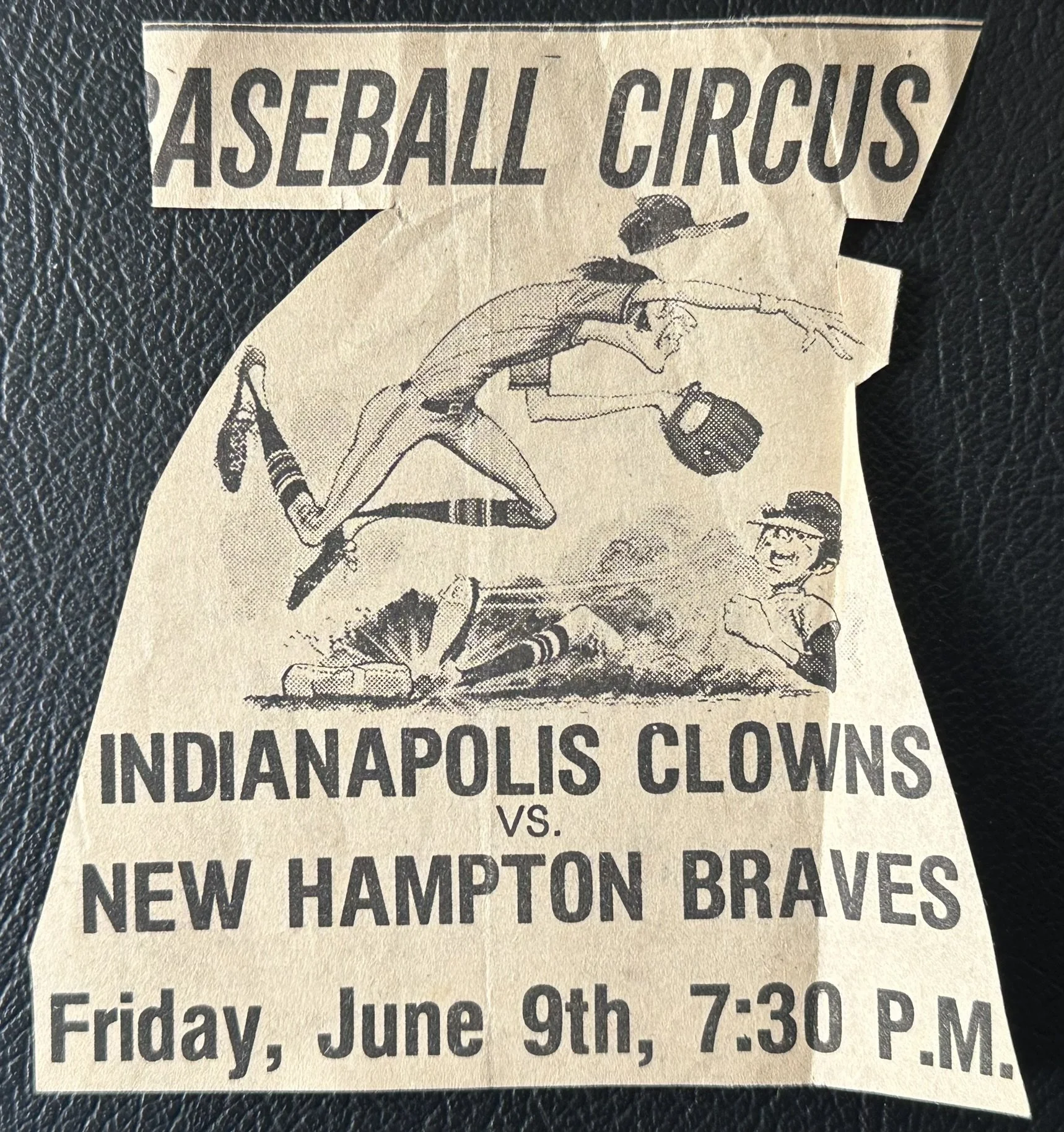

Advertising

George Long would print up hundreds of copies of these blank broadsides at the beginning of each season. Notice on this one it says “48th Season” which was Jay’s first with the team, 1977.

The bottom right corner would be left blank so George could fill it in with the appropriate information for each team/city/date/time to properly promote each individual game.

If he was traveling with the team, he would walk around the town handing these posters out to local businesses and hanging them up where he saw fit. If he wasn’t traveling with the team, he would trust the team to do it, or send posters to the opposing teams/towns in advance.

Hubert “Big Daddy” Wooten

Hubert Wooten, who was born in Goldsboro, North Carolina on September 6, 1944, graduated from Carver High School. He signed a minor league contract with the Vero Beach Dodgers in 1964 where he pitched and played in the outfield. He played for the Clowns from 1965-68.

Wooten, who was only 5’ 8”, said "I've always had power and people wonder how. And I'd tell them, 'It happens when you work on a farm.' When I was a youngster, I had to cut wood, I had to walk behind that mule, and I had to take two 50-pound bags of fertilizer, one in this hand and one in the other, and carry them across the field. I didn't get my power in the gym, I got my power on the farm."

DeWitt “Woody” Smallwood

DeWitt "Woody" Smallwood played from 1950-1954 for the Indianapolis Clowns, the New York Black Yankees, the Philadelphia Stars, and the Birmingham Black Barons.

A teammate of Henry Aaron’s on the Clowns, Smallwood remarked "Aaron could make that tin fence in Winston-Salem talk with his line drive hits."

Reece “Goose” Tatum

Reece “Goose” Tatum was a flashy-fielding showman with the Clowns. At first base, he provided a big target for infielders and entertained the fans with his long arms and a big stretch.

Although better known for his glovework, Tatum started the 1947 All Star game for the West squad and banged out 2 hits in 4 times at the plate.

John Wyatt

John Wyatt played all or part of nine seasons in Major League Baseball, primarily as a relief pitcher. From 1961 through 1969, he played for the Kansas City Athletics (1961–66), Boston Red Sox (1966–68), New York Yankees (1968), Detroit Tigers (1968) and Oakland Athletics (1969).

He began his career in the Negro Leagues playing for the Indianapolis Clowns (1953–55).

Clarence “Choo-Choo” Coleman

Clarence Coleman was born in Orlando, Florida, on August 25, 1937. In 1955, shortly after graduating high school, Coleman signed with the Indianapolis Clowns.

The authors of The Great American Baseball Card Flipping, Trading and Bubble Gum Book, Brendan C. Boyd & Fred C. Harris, had this to say about Coleman:

"Choo-Choo Coleman was the quintessence of the early New York Mets. He was a 5'8", 160-pound catcher who never hit over .250 in the majors, had 9 career home runs, 30 career RBIs, and couldn't handle pitchers. Plus his name was Choo-Choo. What more could you ask for?"

Casey Stengel once complimented Coleman's speed, saying that he'd never seen a catcher so fast at retrieving passed balls.

Paul Casanova

Paulino ("Paul") Ortiz Casanova was a Cuban catcher who played Major League Baseball from 1965 to 1974 for the Washington Senators and Atlanta Braves.

Casanova began his professional baseball career on January 1, 1960, when he was signed as a free agent by the Cleveland Indians. After playing ten minor league games, he was released by the Indians. Casanova was picked back up by the Indians in December, only to be released again in April 1961.

During the 1961 season, he played for the Indianapolis Clowns.

After baseball, Casanova created a baseball academy at his home in Florida. It also became a gathering place for his former teammates and fellow Cuban ball players. Casanova has been described as the glue holding his whole generation of baseball players together.

Hal King

Harold King was a catcher in Major League Baseball and the Mexican League from 1967 to 1979 for the Houston Astros, Texas Rangers, Atlanta Braves, Cincinnati Reds and the Saraperos de Saltillo.

King began his professional baseball career in 1962 with the Indianapolis Clowns, and played for the team through 1964.

Toni Stone

The Clowns were the first professional baseball team to hire a woman to a long-term contract to play competitively, when they signed Toni Stone in 1953. Stone played second base and hit .243.

Clowns owner Syd Pollock was reportedly trying to hire Stone for the Indianapolis Clowns since the close of the 1950 baseball season. While the media reported that she finally agreed to sign on for a staggering $12,000 for 1953, many sources identify that figure as an untruth for publicity purposes. Other reports are that Pollock wanted Stone to play in a skirt or in shorts, and she refused.

A baseball player from her early childhood, she also played for the San Francisco Sea Lions, the New Orleans Creoles, and the Kansas City Monarchs before retiring from baseball in 1954.

Toni Stone in Ebony Magazine from July 1, 1953 (courtesy of Toni Stone family, Negro Leagues Baseball Museum Archives)

Mamie "Peanut" Johnson

Some accounts have Mamie “Peanut” Johnson barnstorming with the Clowns in late 1953, but she was definitely playing full-time in 1954. Johnson had initially attempted to try out for the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League, but was barred due to race.

A pitcher with a slider, circle change, screwball and a curveball she claimed to have learned from Satchel Paige, she did not throw hard but she had good control.

They called the 5-foot-3 (or maybe 5-foot-2) Johnson “Peanut.” Story has it that in her first game pitching for the Clowns, Hank Baylis peered from the batter’s box to the diminutive pitcher on the mound and called, “What makes you think you can strike a batter out? Why, you aren’t any larger than a peanut?” She struck him out, and the nickname stuck.

Johnson is believed to have compiled a 33-8 record on the mound in her time pitching for the Clowns. But she hit, too – the reports vary, but all place her within the range of .260 to .285 for her career batting average.

Connie Morgan

A native of Philadelphia, Connie Morgan graduated John Bartram High School in 1953 and attended William Penn Business Institute. Clowns owner Syd Pollock arranged for Connie to try out during the Clowns’ postseason 1953 tour against Jackie Robinson’s Major League All-Stars, where she was photographed with Jackie.

Morgan joined the Clowns in 1954, playing second base for Hall of Famer Oscar Charleston. She was signed "to a contract estimated at $10,000 per season."

Described as standing 5 feet 4 inches tall and weighing 140 pounds, she was "slated to get the regular female assignment in the starting lineup." On opening day of the 1954 season, "she went far to her right to make a sensational stop, flipped to shortstop Bill Holder and started a lightning double play against the Birmingham Barons."

Women In The Negro Leagues

For decades, women's baseball was just as segregated as the men's game. But Toni Stone, Mamie “Peanut” Johnson and Connie Morgan enjoyed professional opportunities in the Negro Leagues, blazing a trail for the women who would come after them.

Black Women Playing Baseball: An Introduction by Leslie Heaphy

Playing With The Boys: Gender, Race, and Baseball in Post-War America by A.J. Richard

Henry Aaron

Scout Bunny Downs discovered Henry Aaron playing with the Mobile Black Bears, a semipro team, during an exhibition. Aaron was making $3 per game. When he signed his first professional contract with the Clowns in 1953 for $200 a month, he was thrilled.

Aaron flourished with Indianapolis, helping guide the team to the 1952 Negro League World Series crown. In 26 games, he posted a .366 batting average, hit five home runs, and stole nine bases. The series, and the season, allowed Aaron to showcase his range of skills not just for regional scouts, but for several major-league organizations as well.

Following the championship, two telegrams reached Henry – one with an offer from the New York Giants, and a second with an offer from the Boston Braves. Aaron chose the latter, evidently because of a $50-a-month difference in salary, and Boston immediately purchased his contract from Indianapolis. That’s right: the Giants were $50 away from having Willie Mays and Henry Aaron in the same outfield.

Multi-Sport Star

Jay took all sports seriously, whether it was baseball, basketball, or football. When he heard that Henry Aaron was discovered by Major League scouts while playing for the Clowns, though, he turned his intensity up a notch.

“It really gave me a sense of, man, this is a serious venture. If [Henry Aaron] played there and got signed there, then this is not just a little thing.”

Team Historian

While George Long had been running the Clowns for years, he wasn’t always around the players. And even when he was, most of them didn’t really talk to George too much.

Jay mainly learned the history of the Indianapolis Clowns from Birmingham Sam and Bobo, who had each played for the team for years by the time Jay joined.

This photo of the 1943 Clowns team is courtesy of Indiana Historical Society

A Negro League Team

The Indianapolis Clowns were historically a Negro League team, but the Negro American League's 1951 season is generally considered the last true Negro league season.

Most Negro League teams disbanded for good when the Negro American League officially closed its doors in 1952 – three years after it had become the sole Negro major league still in operation.

This photo shows players from the 1947 Clowns team (left to right) Manuel Godínez, Reinaldo Verdes Drake, and Andrés A. Mesa.

Photo courtesy of the Indiana Historical Society

Carrying On The Negro Leagues Tradition

Even though the Negro Leagues were no more, the Clowns kept playing well into the 1980s.

While Jay didn’t and his teammates didn’t consider themselves to be Negro League players, they believed they were carrying on the tradition of the Negro Leagues by continuing to barnstorm like the teams who came before them.

When the team was announced at ballparks, they would say “The Indianapolis Clowns: The Last Of The Negro League Baseball Teams.”

The 1976 movie The Bingo Long Traveling All Stars & Motor Kings is loosely based on the story of the Indianapolis Clowns.

Some Are Called Clowns

You can read a pdf version of Bill Heward’s great book, Some Are Called Clowns by clicking HERE.

Leon Wagner

In order to add authenticity to the baseball scenes, the cast included Leon “Daddy Wags” Wagner, who was a two-time American League all-star. From 1961 to 1963, Wagner averaged 31 home runs and 99 RBI.

With his upbeat nature, big smile, and willingness to laugh, Wagner emerged as a popular figure in the clubhouse.

Wagner portrayed first baseman Fat Sam Popper in The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars and Motor Kings. The film drew heavy criticism for exaggerating the clownish aspects of the Negro Leagues. Perhaps because of the poor reviews, Wagner’s acting career soon fizzled out. He would never again make an appearance in a feature film.

The cast also included Jophrey Brown (who pitched in one game for the 1968 Chicago Cubs, then became a well-respected Hollywood stuntman), as well as Rico Dawson and “Birmingham” Sam Brison, who each played for the Indianapolis Clowns.

Colorful Jerseys

Billy Dee Williams played Bingo Long in the 1976 film The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars and Motor Kings.

While the film’s success introduced the Negro Leagues to a wider audience, the story line’s emphasis on “clowning” reinforced racial stereotypes in baseball.

Billy Dee Williams sported this colorful jersey as Long, the title character who was based on legendary pitcher Satchel Paige.

Throwing between his legs!

Shadow Ball

Jay’s Jersey

Jay was gifted this special Indianapolis Clowns jersey from Birmingham Sam Brison because he was in the act.

If you were in the act, you would get a little bit more money, so Jay got $13 a day. Jay is proud of the fact that he was paid more to play for the Clowns than Henry Aaron was, since Aaron was only paid $200 per month when he was with the team.

King Tut

Richard Elmer King was the famous Clown Prince for the Clowns known as “King Tut.”

King joined Charlie Henry’s Louisville-based Zulu Cannibal Giants in 1934. The Cannibals wore grass skirts, red wigs and face paint.

King was known more for performing pantomime comedy acts than his playing ability. He often worked alongside dwarf Spec Bebop, where the two performed their rowboat routine.

King was also known for his oversized first baseman's mitt, which had been conceived by Ed Hamman. King eventually transitioned away from playing altogether, but remained associated with the Clowns until his retirement.

His illness led to his retirement in the spring of 1959, which left a void with the Indianapolis Clowns.

James “Nature Boy” Williams

By the time James “Nature Boy” Williams joined the Indianapolis Clowns in 1955, the team had become a full-time barnstorming attraction, having dropped out of the Negro American League which itself was in its death throes.

The 6’ 2” 220-pound Williams spent more than a decade with the Clowns and was known for batting barefoot, playing with the large glove (as pictured) and dancing at first base with umpires.

Williams was the first person tasked with replacing King Tut as the Clown Prince after Tut’s retirement. While Williams was popular, the Clowns needed someone with King Tut’s charisma.

Besides, Williams had some health issues of his own. He played the entire 1963 season with his right eye completely blind due to an off-season accident, without even his teammates knowing his condition.

Sam Brison

Enter: Sam Brison.

Given his resemblance to King Tut, Clowns owner Syd Pollock originally billed Brison “King Tut, Jr.” but fans kept asking Sam how his dad was doing, thinking they were asking about the original King Tut, and Sam didn’t have an answer because that wasn’t his dad, and he didn’t want to lie to the fans who genuinely cared about King Tut and were asking about him out of kindness.

When Pollock asked if he just wanted to be called by his name, Brison said: “No, I figure Birmingham Sam will be good. People will ask me about how Birmingham is. I can answer that.”

Brison played (and performed) for the Indianapolis Clowns from 1962 to 1978.

A Great Athlete

“Sam was crazy.” But he was a great athlete. He would get into a new town and hustle the doctors on the golf course, winning extra money for himself and Jay.

Following the example of many members of the Clowns throughout the team’s history, Brison also spent his winters playing basketball, first with Goose Tatum’s Harlem Road Kings, then with the Harlem Globetrotters. On the basketball court, he said he “had a lot of showmanship about me… I did a lot of hollering.”

Here, Sam practices his swing with Clowns pitcher Kurt Christiansen.

“Junior”

Sam used to call Jay “Junior.” When Jay asked why, Sam said it was because Satchel Paige used to call Sam “Junior” so he was just passing on the tradition.

Paige’s last turns on the mound came in 1967, pitching for the Clowns. By his own estimation, he had pitched in about 2,500 games before putting down his glove for good.

Clothing Optional

Sometimes, when you have just the right amount of alcohol in your system, you have one drink more than that and end up making some interesting decisions.

Birmingham Sam wasn’t the only Clowns player to have experienced this phenomenon.

Women

One of the women Jay “met” while playing for the Clowns was Nicki Thomas, who was born Nancy Elizabeth Tritt on March 22, 1954 in Berwyn, Illinois. She is most remembered for being Playboy's Playmate of the Month in March of 1977.

Since the team never stayed in a town for more than 24 hours, Jay said if you met a girl, you literally had to “hit and run.”

Sam Could Play Anywhere

Jay said "Sam could pitch, he could catch, he could play any position on the field... except for mine."

His best position was shortstop, but he was so good that he could play first base while sitting in a chair, still able to reach for baseballs and scoop poor throws despite having a very limited range of motion.

He would also sit at first base and hold the runner on while staying in the chair.

While Sam wasn't a switch hitter, but he would mess with the pitcher before the pitch came by standing backwards in the batter’s box until the pitcher was about to release the ball, then jump around at the last moment and smash the pitch, as seen in the video below.

Ed Hamman

Most of the clowning that took place into the 1970s and 80s had been passed down from generation to generation by Ed Hamman, the player-turned-owner of the Clowns.

An Amazing Talent

In 1969 The Associated Press reported that Brison had secured a spring training tryout with the Boston Red Sox’ Carolina League Winston-Salem franchise.

The Associated Press story incorrectly said the 29-year-old Brison was only 23. Brison said an injury earlier in the spring had led to the cancelation of a tryout with the Cincinnati Reds.

The Rowboat Routine

King Tut and Spec Bebop were the most famous pair of Clowns to perform the rowboat routine, but the routine itself dates back to decades before them.

Here, Nick Altrock (umbrella) and Al Schacht (“The Clown Prince of Baseball”, rowing) perform the routine before Game 1 of the 1925 World Series.

A short clip of the routine as depicted in Bingo Long can be seen below.

Nate “Bobo” Smalls

Nate “Bobo” Smalls was a pitcher who played for the Clowns from 1965 to 1986, a longer tenure than any other player ever had with the team.

Smalls had a great fastball and a really good curveball. But what was probably most impressive about him was the size of his hands, and the control he had when pitching.

Bobo could take three baseballs in one hand, line up three guys like catchers, and he could throw a strike to each one of those guys with the same throw.

His biography can be found in a book called Only The Ball Was White as well as in Some Are Called Clowns.

Steve Anderson

Steve Anderson was a one armed first baseman whose nickname was “Nub.”

At age 6, Anderson was hit by a telephone truck and had his left arm amputated, but that didn’t stop him from playing ball. Billed as “the world’s greatest one-armed player,” Steve fielded this way:

He’d catch the ball, lay the glove on his shoulder in the same motion, and get the ball away as fast as any major leaguer. And the glove never fell off his shoulder.

Some say he could turn a double play and bat with one arm better than most players could with two.

There was a one-armed player in Bingo Long, so you can see how Anderson would have received a throw by watching the clip below.

Rico Dawson

Known for his flashy style and athletic ability, Rico Dawson was an outstanding hitter who batted over .400 in three different seasons at Sterling High School career in Greenville, South Carolina. While playing for the Greenville Black Spinners after his college career, Dawson said he had a “real good game” playing in an exhibition against the Indianapolis Clowns.

After that game, the Clowns offered Dawson a contract to go on the road with them, which he did for two seasons. His association with the team led to him being recommended as an extra for the Bingo Long movie. Despite having no acting experience, Dawson impressed the directors so much that he was given the speaking role of second baseman, Willie Lee Shively.

Reliving Old Memories

Some of them better than others. It’s sad to think what some people find to be an acceptable way to treat someone else.

Hard To Believe

It’s hard to believe you could meet someone like Jay and think anything negative about him. But it’s even harder to believe that there are people out there who would never give themselves a chance to truly meet him in the first place.

Of course, not everyone the Clowns encountered on the road gave them a hard time, but the ones that did are still remembered all these years later.

Imagine showing up to your baseball game, trying your absolute best, and getting beat by a team with a player dressed in a clown suit while they goof around all game. Luckily, most opposing players and fans were in on the bit.

Diffusing The Situation

If there ever was an instance when an opposing fan or player seemed to be taking things too seriously, Birmingham Sam or Bobo would try to incorporate them into the act to lighten the mood so everyone else could keep playing.

The Negro Motorist Green Book

An annual guidebook for African-American road trippers founded and published by New York City mailman Victor Hugo Green from 1936 to 1967.

From a New York-focused first edition published in 1936, Green expanded the work to cover much of North America.

The Green Book became "the bible of black travel" during the era of Jim Crow laws, when open and often legally prescribed discrimination against African Americans and other non-whites was widespread.

Always Smiling

Jay is one of the kindest people I've met since moving to Cleveland. He is always smiling, and he goes out of his way to be supportive and to show up for people.

Here he is with Bob DiBiasio, who is the Senior Vice President of Public Affairs for the Cleveland Guardians, at an event hosted by the Baseball Heritage Museum at Cleveland’s historic League Park.

Nice Facilities

It wasn’t often when the Clowns played in beautiful ballparks with nice facilities, but when they did, the players made sure to take advantage of the ability to shower in the locker rooms.

With how much they always had to drive, the team would sometimes go days without sleeping in a hotel or motel, which means it could also be days without a chance to shower.

When All Else Fails, Drink A Beer

If everyone has to be stuck in the car without showering for days, you might as well get some beer.

“We’ll Just Find Somebody Else”

If a player missed the team bus, they were a “hog cutter” and had most likely played their last game with the Clowns.

The team had too much traveling to do, too many games to play, to also have to worry about keeping everyone in line. If you couldn’t hold yourself accountable to be on the bus by the time it left for the next town, the team would just find someone else on the road to replace you.

Sioux Empire College

After Jay played his first season with the Clowns in 1977, he went to Sioux Empire College in Haywarden, Iowa. The school was founded in 1965, with the first semester being held in the fall of 1967.

A few of Jay’s teammates on the Sioux Empire team were guys he traveled with on the Indianapolis Clowns.

Big George

Big George Sanders was a pitcher who was similar to J.R. Richard.

“The Saga of J.R. Richard’s Debut: Blowing Away 15 Sticks at Candlestick” by Dan VanDeMortel

Greg Stockton

Greg Stockton was the team’s catcher.

Mike Coco

Mike Coco was the team’s second baseman.

Mark Glatter

Mark Glatter was a teammate of Jay’s at Sioux Empire who also played with the Clowns sometimes.

Tom Farr

Tom Farr was a teammate of Jay’s at Sioux Empire who also played with the Clowns sometimes.

Bob Cerv

Bob Cerv was Jay’s manager when he played for Sioux Empire College.

Cerv played Major League Baseball from 1951 through 1962, most notably spending 9 seasons with the Yankees, winning a World Series with the team in 1956 and being named an All-Star in 1958 as a member of the Athletics.

Prior to his professional career, Cerv was a collegiate baseball and basketball player at the University of Nebraska, and served in the U.S. Navy during World War II.

Roommates

During the 1961 season, Cerv lived in a $251-per-month (equivalent to $2,658 in 2025) apartment in Queens with Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris.

Cerv and Maris often roomed together, because the Yankees’ manager didn’t understand Maris’ personality and wanted Cerv, the seasoned veteran, to help him figure it out.

“Roger asked me ‘Why are you my roommate now?’ when I first roomed with him,” recalls Cerv. “I told him, ‘To tell the truth, the skipper wants to know what makes you tick.’ We were best buds after that.”

Not Afraid To Fight

“[Billy] was a ballplayer. A little hotheaded, though. He didn’t take any crap,” said Cerv, of Billy Martin.

Billy may have had the mouth that started the fights, but Bob Cerv wasn’t afraid to come in and finish them. On May 17, 1958, Cerv fractured his jaw in this home plate collision with Detriot Tigers catcher Red Wilson.

Doctors said Cerv would be out for six weeks. He was back three days later. After six weeks playing with his jaw wired shut, Cerv was still batting .310 and leading the American League in home runs and RBIs.

The Saturday Evening Post covered the story in 1958.

Angie Dickinson

Angie Dickinson began her career on television, and appeared in more than 50 films.

Dickinson's big-screen breakthrough role came in Howard Hawks' Rio Bravo (1959), in which she played a flirtatious gambler called "Feathers" who becomes attracted to the town sheriff played by Dickinson's childhood idol John Wayne.

Bob Cerv was having an affair with Angie Dickinson at one point during his career. Cerv injured his knee during a game, so Angie came rushing to the hospital to check on him. When she arrived, she was greeted in the room by Bob’s wife, Phyllis. Yikes.

Here is Angie Dickinson in A Fever in the Blood (1961).

Regor Siram

Bob Cerv and Regor Siram (Roger Maris, spelled backward) light up cigars at Yankee Stadium on August 28, 1960, as both celebrated additions to their families. Maris’ wife gave birth to a boy in Kansas City, while Mrs. Cerv gave birth to the couple’s 8th child, a girl, on August 26.

Bob and Phyllis had 10 children, all of whom went through college, 32 grandkids, and 11 great-grandchildren. So there were lots of cigars.

Mickey Mantle

Bob Cerv said Mickey Mantle was one of the fastest players he’d ever seen. Mickey holds the record for fastest time from home to first, clocking in at 3.1 seconds.

Cerv and Mantle were teammates from 1951-1956, again in 1960, and for one more stint from 1961-62. Cerv saw Mickey before his first knee injury in the 1951 World Series, and when his body was still young enough to recover from his many knee issues.

Though Mickey was one of the fastest players in the game in his prime, the Yankees preferred that he didn't run because of his persistent leg injuries. He stole just 153 bases in his career, with a career high of 21 in 1959.

Don Larsen

After getting pounded for 4 runs in 1.2 innings in Game 2, Don Larsen spiraled into a three-day depression. Larsen went out with a couple of newspaper pals, brothers Milton and Arthur Richman, the night before the fifth game. Legend has it Larsen was drunk when he showed up for Game 5 of the 1956 World Series.

“I had no idea I was starting that game until I came to the park that day,” Larsen said. “When I got to the park there was a baseball in my shoe. That was the tradition in those days.”

Larsen ended up throwing a perfect game, the only perfecto in postseason history. It was by far the most memorable moment in his 14-year career.

Casey Stengel

At spring training in St. Petersburg, Florida in 1956, Don Larsen fell asleep while driving back to the team hotel, lost control of his convertible, and crashed into a palm tree. It was 5 a.m. He escaped with a chipped tooth and a $15 ticket.

When manager Casey Stengel (seen here, center, with Bob Cerv on the right), a notorious boozer himself in his playing days, was asked what his pitcher was doing out at that ungodly hour, Stengel told the press with a straight face “he went out to mail a letter.”

Bob Cerv wanted his players to utilize an open stance at the plate so they could see the ball with both eyes. Here are some of his credentials.

Belvie Kennerly

Jay always played center field. But when Bob Cerv brought in new recruit Belvie Kennerly, he asked Jay to move over to left so Belvie could play center. Jay obliged.

Jay is seen here seated in the middle row all the way on the left. Belvie is in the center of that same row, and Belvie’s brother, James, is seated next to him.

“Bunt The Damn Ball!”

Sometimes Jay and Belvie would “miss” a bunt sign from the dugout and choose to swing away. The next pitch, Bob Cerv would tell the infielders they were getting the bunt sign again, and if they “missed it” this time, they’d be sitting the rest of the game.

Easy To Listen

Jay said it was easy to listen to what Bob Cerv was telling the team because he had not only been to the Majors, but had a long career with impressive accolades. Cerv knew what it took to get to where those players wanted to be. You would be crazy not to listen.

Was It Enough Money?

In 1971, Indianapolis Clowns players received no salary, and received just $4 a day in meal money. By the time Jay was on the team 6 years later, players were being paid $5 a day in meal money.

Jay personally earned an extra $5 because he was in the Shadow Ball routine and part of the show. And if the team didn't stop to get a hotel or a motel at night, each player would get $2 more of what was called "riding money" for sleeping in the car while the team drove to the next town.

While the team may have joked about how little the players were being paid (this image once appeared in an Indianapolis Clowns program), Jay acknowledges that the amount the players made simply wasn’t enough.

Old Grand Dad

Jay was able to save a little bit of money on the road because he wasn’t a big drinker or smoker. Some other players weren’t as fiscally responsible.

Birmingham Sam liked to smoke cigarettes and drink Old Grand Dad bourbon, but he could usually afford it because he was getting paid to be the Clown Prince, and hustling doctors on the golf course, to boot.

Money Manager

When George Long wasn’t actively traveling with the team to handle it himself, he appointed Mike Coco to manage the money for the team.

From taking care of the payouts with the other teams at the end of games, to divvying up the money to the other Clowns players, Coco could be trusted.

Here he is with Birmingham Sam.

In The Owner’s Best Interest

When a Major League team would sign a player from the Indianapolis Clowns, the owner of the team would get 2% of the value of the Major League contract that the player would sign as a kick back.

So when the Braves signed Henry Aaron for $10,000, the owner of the Clowns got $200. At that time, the owner was Syd Pollock, seen here shaking hands with Henry Aaron.

While that $200 was valuable to the team, it also created a hole in the roster by shipping one of the team’s best players off to the big leagues.

It was made abundantly clear that everyone on the team was replaceable, though. From the last guy on the bench, to the Clown Prince, himself. No one was bigger than the team.

Aaron’s Sale

This letter outlines the sale of Henry Aaron by the Indianapolis Clowns to the Braves organization.

“…lowest deal I would consider on shortstop HENRY AARON would be $10,000., with $2500. down payment, balance to be paid after 30-day look, regardless of classification he was started in, and salary of $350. monthly.”

“I feel this youngster is another Ted Williams in the hitting department, and can hit to all fields as well as lay down bunts, and his fielding right now leaves little to be desired, outside of a bit of polishing on getting off his throws.”

Grand Junction, CO

Despite a couple miscues in the outfield due to the thin air, Jay’s favorite place to play was Grand Junction, Colorado, against the Grand Junction Eagles.

Here he is (center) goofing around with Clowns teammates Darryl Herring (left) and Big George Sanders (right).

Paul Molitor

Paul Molitor was an All-Big Ten and All-American shortstop for the Minnesota Golden Gophers in 1976 and 1977. At the U of M, Molitor had a career batting average of .350, and led his team to the Big Ten championship and a College World Series appearance in 1977.

He played for the Grand Junction Eagles, but was called up to the big leagues to play for Milwaukee a couple weeks before Jay Valentine had a chance to play against him.

Molitor played 21 seasons in the Major Leagues with the Milwaukee Brewers, Toronto Blue Jays and Minnesota Twins. In 1993 he helped lead the Blue Jays to a World Series title, earning World Series MVP honors.

On September 16, 1996, against the host Kansas City Royals, Molitor became the 21st player in MLB history to hit 3,000 hits, the first to hit that mark with a triple.

The .306 career hitter and seven-time All-Star retired in 1998. He was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2004.

Kevin Schoendienst

Kevin Schoendienst, the son of Cardinals legend and Hall of Famer Red Schoendienst, played against Jay in Grand Junction, Colorado. They all went out drinking together after the game, which wasn’t uncommon.

Steve Bartkowski

Steve Bartkowski was a quarterback in the NFL for the Atlanta Falcons (1975–1985), the Washington Redskins (1985), and the Los Angeles Rams (1986). He was a two-time Pro Bowl selection.

Bartkowski played college football for the California Golden Bears, earning consensus All-American honors as a senior in 1974. He was selected by the Falcons with the first overall pick of the 1975 NFL draft.

In addition to playing football, Bartkowski was also an All-American baseball player at first base for the Bears. He was drafted by the Kansas City Royals in the 33rd round of the 1971 MLB June Amateur Draft from Emil R. Buchser HS (Santa Clara, CA) and again by the Baltimore Orioles in the 19th round of the 1974 MLB June Amateur Draft from University of California, Berkeley (Berkeley, CA).

Bartkowski played baseball for Bob Cerv in Kansas, and was teammates with Ron Guidry on that team.

Nice Ballparks

Jay feels lucky to have played in some really nice ballparks over the years.

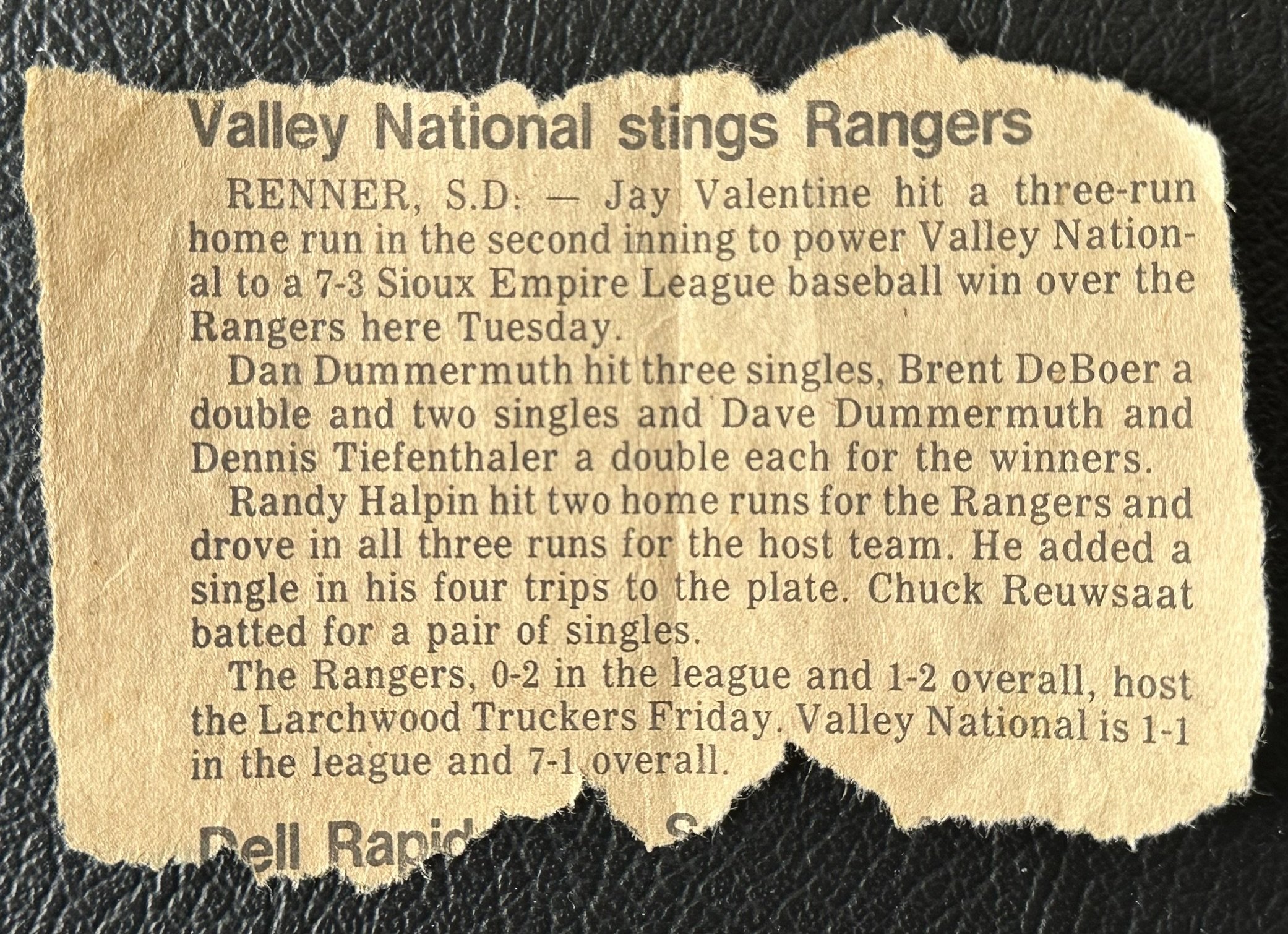

When Jay was in college, he played summer ball with this team sponsored by Valley National Bank for multiple years. Jay is top row, all the way on the right in this photo.

Packer Stadium

Also known as Sioux Falls Stadium in South Dakota, this was Jay’s home ballpark when playing for the summer league team.

Originally opened in 1941, the stadium has been the home field of the Sioux Falls Canaries of the American Association since 2013.

It was also the home field of the Sioux Falls Packers (Northern League, 1966-1971), the Sioux Falls Canaries (Northern League, 1993-2005), the Sioux Falls Canaries (American Association, 2006-2009), the Sioux Falls Fighting Pheasants (American Association, 2010-2012), and the St. Paul Saints (American Association, 2020).

Ken Griffey, Sr.

Ken Griffey, Sr. played for the Sioux Falls Packers in 1970. Sioux Falls was the second-lowest rung on the Reds’ minor-league ladder. Jay says he heard many stories of the racism Ken faced while playing there.

Ballpark Conditions

Jay remembers most of the ballparks he played in being nice, but the ones which weren’t as in good of shape tended to be in the southern states.

Clowns’ 48th Season

Jay played for the Indianapolis Clowns in the 48th and 49th seasons, which were 1977 and 1978, respectively.

Sioux Empire College

After each of his two seasons with the Clowns, Jay played for Sioux Empire College.

Then in 1979 and 1980, Jay played for Sioux Falls College, which is now called the University of Sioux Falls.

After College

Jay didn’t think he was necessarily going to be a ballplayer after he graduated college. He majored in Speech Communications and Theater, and thought after his baseball career was over, he would either become an actor, or do something in sports broadcasting.

Jay is pictured here in the center, acting in a play during college.

Home Runs

Jay wasn’t a power hitter, but he did hit some big home runs in his career. At least a couple of three-run home runs (one of which was written about in the newspaper), and a grand slam are some of the highlights of his playing days.

Summer League

Jay’s grand slam came in Sioux Falls while playing in front of his home crowd at Sioux Falls College.

Here he is (top row, second from left) in a Summer League team photo for his Valley National Bank team.

Freedom

When asked what the best thing about being a ballplayer for the Indianapolis Clowns was, Jay responded with “the freedom.”

Being able to do your own thing, without people telling you what to do, is a great feeling.

“You did whatever you wanted to do.”

College Eligibility

Even though he was only making $12-13 a day playing for the Clowns, he was still being paid, technically making him a professional.

That should have ended his college eligibility, but luckily, no one found out and he was able to play for Sioux Empire and Sioux Falls.

Pride

Jay said he is proud of his life’s accomplishments. After spending the day talking with him, and sitting together going through all of his old photos, newspaper clippings, and scrapbooks, that was extremely evident.

Advice For His Younger Self

Jay took the game seriously. He eats, sleeps, and drinks baseball. While he didn’t happen to be at the right place at the right time to achieve his ultimate dream of making it to the Major Leagues, Jay was in Fort Lauderdale at 18 years old, sharing the field with Major League players and in front of Major League managers, coaches, and scouts.

This is the letter Jay got from the Baltimore Orioles telling him to go play for Bob Cerv.

Bonnie

Jay’s sister, Bonnie, who drove him from Ohio to Iowa to try out for the Indianapolis Clowns, and then drove him from Ohio to Iowa AGAIN to take him to Sioux Empire College.

Now that’s someone you can count on.

50 States

At the time of this recording, I have been to 49 states, only missing Hawaii. By far and away, the person who has been with me in the most different states is my mom.

Here we are at Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater in March of 2016.

Supportive Family

Jay was lucky in that he had support from his family to chase his dreams. Here he is with his three brothers and sister.

Travel

As if traveling across the country with a baseball team on a bus wasn’t hard enough already, but then they have to deal with racism, too?

Jay’s Man Cave

Jay was gracious enough to invite me over to his house so we could record this interview.

It is insane to me that I am friends with someone who has had a run in with the Ku Klux Klan.

A Big Kid At Heart

Jay’s personality and kind heart makes it easy to want to be around him.

Broadsides

This broadside is from 1969, the Indianapolis Clowns’ 40th season.

Birmingham Sam

This is a close up shot of one of the broadsides Jay has in his personal collection. This one was signed by Jay’s friend, teammate, and roommate, Birmingham Sam.

Pranks

This isn’t a story Jay told while we were rolling, but afterward when we were going through the pictures together, he found this one and told me the story behind it.

His teammates woke him up one morning and threw a Burger King bag on his bed, saying they got him breakfast. Jay opened the bag, and inside was the snake you can see on the railing in this photo.

Boys will be boys.

The Bingo Long Traveling All Stars & Motor Kings

If you have never seen the movie before, I genuinely do recommend it. Now that you have listened to this interview with Jay and heard him talk about his experiences barnstorming with the Indianapolis Clowns, I think you will understand and appreciate a lot of the subtleties of the film, especially when it comes to the showmanship of the team.

Any time there was a closeup of what was supposed to be Billy Dee Williams’ character’s hands in the movie, the camera was actually cutting to the hands of Birmingham Sam Brison.

This was the modified newsreel which played at the beginning of the movie. Clearly using real Negro League footage, the voiceover stretches the truth to apply to the movie.

Soundtrack

I had the soundtrack to the movie on vinyl well before I had ever seen the movie. A large chunk of my vinyl collection is made up of baseball-related records, so any time I see one I don’t have, I am tempted to buy it.

Goose Tatum

Goose Tatum was basketball’s original clown prince. He was discovered by Globetrotters owner Abe Saperstein on – of all places – the baseball diamond.

Goose was a tremendous athlete, with physical skills that matched his timing and sense of humor.

Tatum choreographed several of the famous Globetrotter reams including hiding in the crowd, spying on the opposition’s huddle, and feinting only to be revived by the foul smell of his own shoe.

He was a serious basketball player, though, perfecting a hook shot that he often shot without even looking at the basket.

In 1948, Tatum and the Globetrotters upset the George Mikan-led Minneapolis Lakers in a one-game showdown for the ages. The article see here appeared in a 1948 newspaper.

Meadowlark Lemon

Few athletes have impacted their sport on a worldwide level more than Meadowlark Lemon.

Perhaps the most well-known and beloved member of the Harlem Globetrotters, Lemon played in more than 16,000 games – 7,500 consecutively – for the Globetrotters in a career that began in 1954 and lasted until 1978.

Known as the “Clown Prince of Basketball,” Lemon’s favored “can’t miss” halfcourt hookshot and comedic routines were performed in more than 70 countries around the globe, entertaining millions of fans, Presidents, Kings, Queens, and even Popes.

As a basketball performer, Lemon’s goal was always the same – entertainment, laughter, and fun.

Lemon was a 2003 inductee into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame.

Wilt Chamberlain

One of the most famous and dominant players in Harlem Globetrotters history, Wilt "The Stilt" Chamberlain began his professional career in 1958 when the Globetrotters signed the University of Kansas standout to one of the largest contracts in sports.

Following his Globetrotter career, Chamberlain starred in the NBA from 1959 through 1973, playing for the Philadelphia/San Francisco Warriors, the Philadelphia 76ers, and the Los Angeles Lakers.

During his NBA career, his dominance brought on many rules changes, including widening the lane, introducing offensive goaltending and revising rules governing free throw shooting.

Toni Stone in the July 1, 1953 issue of Ebony Magazine (courtesy of the Toni Stone family, Negro Leagues Baseball Museum Archives)

Satchel Paige

Satchel Paige began his professional career in the Negro Leagues in the 1920s after being discharged from reform school in Alabama. The lanky 6-foot-3 right-hander quickly became the biggest drawing card in Negro baseball, able to overpower batters with a buggy-whipped fastball.

Paige, a showman at heart, bounced from team-to-team in search of the best paycheck – often pitching hundreds of games a year between regular Negro Leagues assignments and barnstorming opportunities.

At the age of 42, Paige made his American League debut when Bill Veeck signed him to a contract with Cleveland on July 7, 1948.

Paige was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1971.

Josh Gibson

The applause Josh Gibson received should have been louder. He was considered the best power hitter of his era in the Negro Leagues and perhaps even across the entire sport. The legend of Gibson’s power has always been larger than life.

His introduction to organized baseball came at age 16 when he joined the Gimbels A.C. He became a professional by accident July 25, 1930 while sitting in the stands. When Homestead Grays catcher Buck Ewing injured his hand, Gibson was invited to replace him because his titanic home runs were already well known in Pittsburgh.

Gibson’s natural skills were immense. His powerful arm, quick release and agility made base runners wary of trying to steal.

Gibson was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1972.

James “Cool Papa” Bell

Cool Papa Bell may well have been the fastest man ever to play the game of baseball.

The most colorful story of his legendary speed was one told by Satchel Paige, who said that Cool Papa was so fast he could flip the light switch and be in bed before the room got dark. But stories of his base running speed are legion, advancing two and even three bases on a bunt, beating out tappers back to the pitcher, and also playing a shallow center field – because his speed allowed him to catch up to just about anything out there.

He was a member of three of the greatest Negro League teams in history, winning three championships each with the St. Louis Stars, the Pittsburgh Crawfords, and the Homestead Grays.

Bell was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1974.

But There Were Others…

From the game’s earliest days, Black ballplayers have excelled on the diamond while fighting for equality and justice.

The following National Baseball Hall of Fame inductees spent all or part of their careers in

organized Black baseball - including the Negro Leagues - before, during and after

segregation prohibited many of them from playing in the American League or National League.

Where Can You Learn More?

In addition to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, New York, there are a few other great museums preserving Negro League baseball history.

The Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, Missouri

The Baseball Heritage Museum at Cleveland’s historic League Park

The Negro Southern League Museum in Birmingham, Alabama

Bob Cerv

If Bob Cerv looked like this and could land Angie Dickinson, imagine how hard it must have been for Mickey Mantle to stay faithful once he got a couple drinks in him.

David Wells

On May 17, 1998, David Wells pitched the 15th perfect game in MLB history. Pitching against the Twins at Yankee Stadium in front of 49,820 fans, Wells threw the perfect game while being hung over, calling it a "raging, skull-rattling" hangover.

“I went to the park, I was a wreck. I mean, I was a wreck. (David Cone) told me, he goes, you need to go to Monahan’s office to get away from everybody, you stink. So I just started chewing gum, drinking a lot of water and coffee, about ten trips to the bathroom. My stomach was boiling over pretty good. I don’t know, at about 11:30 I had a pancake in there from the spread and I felt a little bit better but I was still a wreck.”

“I knew if I had a short outing, I would’ve gotten in a lot of trouble,” Wells said. “A lot of people knew I was pretty hammered.”

His outing was as short as a 9-inning complete game could be: 27 batters. He didn’t get in any trouble.

Bachelor

Jay wasn’t only responsible for himself. He also owned this Siberian Husky for over a decade, his buddy Bachelor.

Join Our Email Newsletter

It’s free, and it’ll give you some bonus content throughout the month that you won’t get from the podcast episodes or by following any of our other social media platforms.

We put out new issues on the second Friday and the fourth Friday of every month. No more, no less.

Rose Colored Glasses?

We now look back fondly on the Ethiopian / Indianapolis Clowns and the style of baseball they played in the 1930s and 40s, but many Negro League players themselves deeply resented the comic image the Clowns portrayed at the time.

Jim “Fireball” Cohen

Jim “Fireball” Cohen was a righthanded pitcher who made his debut in 1946 and pitched for the team through 1952. He threw a fastball, curveball, slider, changeup and knuckleball.

In 1948, Cohen was selected to play in the East–West All-Star Game. He played in the Venezuelan League in the winter of 1948-1949, and had a 2-3 record with a 3.64 ERA for the 1950 Clowns.

He drove the team bus and was the business manager for Indianapolis in addition to pitching before he retired.

Reinaldo Drake

Reinaldo Drake was a Cuban-born center fielder who played for and even managed the Clowns at points from 1945 through 1954.

A native of Havana, Drake was selected to the East-West All-Star Game in 1953, and later played minor league baseball for the Yakima Braves in Washington state.

Ray Neil

Ray Neil was a second baseman and played his entire career for the Clowns franchise, beginning in 1941 when they were still known as the Ethiopian Clowns.

He moved with the team to Cincinnati in 1943, and played for the Indianapolis Clowns until he retired following the 1954 season. He was among the Negro American League’s top batters in 1953.

In the 1953 East-West Game, Neil hit third for the East and was their brightest light in a 5-1 loss. He went 3 for 3 with a triple, and a run, getting half of the East's hits. Neil also scored the East’s lone run when he connected off Sam (Buddy) Woods and came around on a hit by Henry Kimbro two batters later.

In his autobiography, Henry Aaron (a teammate of Neil's on the 1952 Clowns) posits that Neil might have been too flashy a player for a part of the country that had never had a black player yet.

Buster Haywood

The 1952 championship squad also featured Albert “Buster” Haywood, who played for the Clowns in both Indianapolis and Cincinnati. Haywood was primarily a catcher during his playing career.

In 1941, the Clowns won 125 games during the regular season, as well as the post-season Denver Post Tournament, with Haywood winning MVP.

The Virginia native hit .288 for the 1943 Cincinnati Clowns, splitting the catching duties with Pepper Bassett. He hit .270 as the starter for the Cincinnati/Indianapolis Clowns in 1944, then was a backup again in 1945.

Haywood backed up Sam Hairston as catcher in 1948, and began a stint as manager of the Clowns - a job he would hold until he left the team after the 1953 season. He was the player/manager for the Memphis Red Sox in 1954 before retiring.

He helped discover Henry Aaron in 1951 when the Clowns played against him on the semipro Mobile Black Bears, then became Aaron’s first manager in professional baseball on the 1952 Clowns. Haywood also managed the East team in three consecutive East-West Games from 1951 through 1953.

Henry Aaron

The Clowns had signed Aaron on November 20, 1951, after local scout Ed Scott saw the skinny 17-year-old infielder.

Aaron didn’t even know how to properly hold a bat, placing his lead hand on top until a coach corrected him and showed the eventual home run king how to produce more power.

The kid from Mobile, Alabama only spent one season in the Negro Leagues before signing a contract with the Milwaukee Braves’ organization, leaving the Clowns after their 1952 championship season.

Horace Garner

Outfielder Horace Garner also played for the Clowns.

Along with Henry Aaron and Felix Mantilla, Garner integrated the South Atlantic League in 1953 when the trio played for the Jacksonville Braves.

Garner spent ten seasons in the minor leagues, batting .321 with 1,115 hits, 190 doubles, 37 triples and 157 home runs in 997 games.

Pee Wee Jenkins